According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, nearly 4 in 10 fourth graders read below the basic level. To help these struggling readers improve their skills, the nation's 16,000 school districts are spending hundreds of millions of dollars on often untested educational products and services developed by textbook publishers, commercial providers, and nonprofit organizations. Yet we know little about the effectiveness of these interventions in the school environment. Which ones work best, and for whom? Do they have the potential to close the reading gap between struggling and average readers?

To provide the nation's policymakers and educators with credible answers to these questions, the Haan Foundation for Children, the Florida Center for Reading Research, Mathematica Policy Research, the American Institutes for Research, the Allegheny Intermediate Unit, and the Institute of Education Sciences are collaborating to carry out the Power4Kids evaluation. Conducted just outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny Intermediate Unit, the evaluation is assessing the effectiveness of either substantial parts or all of four widely used programs for elementary school students with reading problems: Corrective Reading, Failure Free Reading, Spell Read P.A.T., and Wilson Reading. The interventions for the evaluation were structured to offer about 100 hours of pull-out instruction in small groups of three students during one school year.

This model supports the heralded 3-Tier approach to reading instruction:

while building vocabulary.

while building vocabulary.The Power4Kids randomized controlled trial consists of an impact study, an implementation study, and a functional neuroimaging study. Nearly 800 children are included in the study. We have administered multiple rounds of reading achievement tests to these children; conducted surveys of their parents, teachers, and principals; and collected school records data, including test scores from the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment. This Power4Kids interim report presents impacts at the end of the intervention year, and a final report will present impacts at the end of the following school year.

Power4Kids

is funded and supported by a unique partnership dedicated to finding solutions to the devastating problem of reading failure.

Power4Kids

is funded and supported by a unique partnership dedicated to finding solutions to the devastating problem of reading failure.

Power4Kids

Partners

Funding Partners

|

|

Executive Management

Power4Kids Reading Initiative

Cinthia Haan, Haan Foundation for Children

Principal Investigator

Joseph K. Torgesen, Florida Center for Reading Research at Florida State University

Co-Principal Investigator, Impact Study Component:

David Myers, Mathematica Policy Research,

together with Wendy Mansfield, Elizabeth Stuart, Allen Schirm, and Sonya Vartivarian

Principal Investigator, FMRI Brain Imaging Component

Marcel Just, Carnegie Mellon University,

together with Co-PI's John Gabrieli, Stanford University, and Bennett Shaywitz, Yale University

Executive Director, School-Management Study Component

Donna Durno, Allegheny Intermediate Unit,

together with Rosanne Javorsky

Co-Principal Investigator, Fidelity and Implementation Study Component

George Bornstedt, American Institutes for Research,

together with Fran Stancavage

Additionally, we acknowledge the support and direction throughout the study from Dr. Audrey Pendleton of the Institute of Education Sciences

Scientific Board of Directors

|

|

|

Education Board of Directors

|

|

|

Neuroscience Board of Directors

|

|

|

Advisors

|

|

|

Congressional Support

|

|

|

Corporate Sponsors

|

|

|

Contract No.: CORPORATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT Reference No.: 8970-400 OF POLICY EVALUATION

| Joseph Torgesen, Florida Center for Reading Research | Fran Stancavage, American Institutes for Research | |

|

David Myers, Allen Schirm, Elizabeth Stuart, Sonya Vartivarian, and Wendy Mansfield, Mathematica Policy Research | Donna Durno and Rosanne Javorsky, Allegheny Intermediate Unit | |

| Cinthia Haan, Haan Foundation |

Submitted to:

Institute of Education Sciences Washington, DC Project Officer: Audrey Pendleton |

Submitted by:

600 Maryland Ave., SW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20024-2512 Telephone: (202) 264-3469 Facsimile: (202) 264-3491 |

EVALUATION PURPOSE AND DESIGN

Conducted just outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny Intermediate Unit (AIU), the evaluation is intended to explore the extent to which the four reading programs can affect both the word-level reading skills (phonemic decoding, fluency, accuracy) and reading comprehension of students in grades three and five who were identified as struggling readers by their teachers and by low test scores. Ultimately, it will provide educators with rigorous evidence of what could happen in terms of reading improvement if intensive, small-group reading programs like the ones in this study were introduced in many schools. improvement if intensive, small-group reading programs like the ones in this study were introduced in many schools.

This study is a large-scale, longitudinal evaluation comprising two main elements. The first element of the evaluation is an impact study of the four interventions. This evaluation report is addressing three broad types of questions related to intervention impacts:

To answer these questions, the impact study was based on a scientifically rigorous design-an experimental design that uses random assignment at two levels: (1) 50 schools from 27 school districts were randomly assigned to one of the four interventions, and (2) within each school, eligible children in grades 3 and 5 were randomly assigned to a treatment group or to a control group. Students assigned to the intervention group (treatment group) were placed by the program providers and local coordinators into instructional groups of three students. Students in the control groups received the same instruction in reading that they would have ordinarily received. Children were defined as eligible if they were identified by their teachers as struggling readers and if they scored at or below the 30th percentile on a word-level reading test and at or above the 5th percentile on a vocabulary test. From an original pool of 1,576 3rd and 5th grade students identified as struggling readers, 1,042 also met the test-score criteria. Of these eligible students, 772 were given permission by their parents to participate in the evaluation.

The second element of the evaluation is an implementation study that has two components: (1) an exploration of the similarities and differences in reading instruction offered in the four interventions and (2) a description of the regular instruction that students in the control group received in the absence of the interventions and the regular instruction received by the treatment group beyond the interventions.

Test data and other information on students, parents, teachers, classrooms, and schools is being collected several times over a three-year period. Key data collection points pertinent to this summary report include the period just before the interventions began, when baseline information was collected, and the period immediately after the interventions ended, when follow-up data were collected. Additional follow-up data for students and teachers are being collected in 2005 and again in 2006.

THE INTERVENTIONS

We did not design new instructional programs for this evaluation. Rather, we employed either parts or all of four existing and widely used remedial reading instructional programs: Spell Read P.A.T., Corrective Reading, Wilson Reading, and Failure Free Reading.

As the evaluation was originally conceived, the four interventions would fall into two instructional classifications with two interventions in each. The interventions in one classification would focus only on word-level skills, and the interventions in the other classification would focus equally on word-level skills and reading comprehension/vocabulary.

Corrective Reading and Wilson Reading were modified to fit within the first of these classifications. The decision to modify these two intact programs was justified both because it created two treatment classes that were aligned with the different types of reading deficits observed in struggling readers and because it gave us sufficient statistical power to contrast the relative effectiveness of the two classes. Because Corrective Reading and Wilson Reading were modified, results from this study do not provide complete evaluations of these interventions; instead, the results suggest how interventions using primarily the word-level components of these programs will affect reading achievement.

With Corrective Reading and Wilson Reading focusing on word-level skills, it was expected that Spell Read P.A.T. and Failure Free Reading would focus on both word-level skills and reading comprehension/vocabulary. In a time-by-activity analysis of the instruction that was actually delivered, however, it was determined that three of the programs-Spell Read P.A.T., Corrective Reading, and Wilson Reading-focused primarily on the development of word-level skills), and one-Failure Free Reading-provided instruction in both word-level skills and the development of comprehension skills and vocabulary.

MEASURES OF READING ABILITY

Seven measures of reading skill were administered at the beginning and end of the school year to assess student progress in learning to read. As outlined below, these measures of reading skills assessed phonemic decoding, word reading accuracy, text reading fluency, and reading comprehension.

For all tests except the Aimsweb passages, the analysis uses grade-normalized standard scores, which indicate where a student falls within the overall distribution of reading ability among students in the same grade. Scores above 100 indicate above-average performance; scores below 100 indicate below-average performance. In the population of students across the country at all levels of reading ability, standard scores are constructed to have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15, implying that approximately 70 percent of all studentsí scores will fall between 85 and 115 and that approximately 95 percent of all studentsí scores will fall between 70 and 130. For the Aimsweb passages, the score used in this analysis is the median correct words per minute from three grade-level passages.

IMPLEMENTING THE INTERVENTIONS

The interventions were implemented from the first week of November 2003 through the first weeks in May 2004. During this time students received, on average, about 90 hours of instruction, which was delivered five days a week to groups of three students in sessions that were approximately 50 minutes long. A small part of the instruction was delivered in groups of two, or 1:1, because of absences and make-up sessions. Since many of the sessions took place during the student's regular classroom reading instruction, teachers reported that students in the treatment groups received less reading instruction in the classroom than did students in the control group (1.2 hours per week versus 4.4 hours per week.). Students in the treatment group received more small-group instruction than did students in the control group (6.8 hours per week versus 3.7 hours per week). Both groups received a very small amount of 1:1 tutoring in reading from their schools during the week.

Teachers were recruited from participating schools on the basis of experience and the personal characteristics relevant to teaching struggling readers. They received, on average, nearly 70 hours of professional development and support during the implementation year as follows:

According to an examination of videotaped teaching sessions by the research team, the training and supervision produced instruction that was judged to be faithful to each intervention model. The program providers themselves also rated the teachers as generally above average in both their teaching skill and fidelity to program requirements relative to other teachers with the same level of training and experience.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDENTS IN THE EVALUATION

The characteristics of the students in the evaluation sample are shown in Table 1 (see the end of this summary for all tables). About 45 percent of the students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches. In addition, about 27 percent were African American, and 73 percent were white. Fewer than two percent were Hispanic. Roughly 33 percent of the students had a learning disability or other disability.

On average, the students in our evaluation sample scored about one-half to one standard deviation below national norms (mean 100 and standard deviation 15) on measures used to assess their ability to decode words. For example, on the Word Attack subtest of the Woodcock Reading Mastery Test-Revised (WRMT-R), the average standard score was 93. This translates into a percentile ranking of 32. On the TOWRE test for phonemic decoding efficiency (PDE), the average standard score was 83, at approximately the 13th percentile. On the measure of word reading accuracy (Word Identification subtest for the WRMT-R), the average score placed these students at the 23rd percentile. For word reading fluency, the average score placed them at the 16th percentile for word reading efficiency

TOWRE SWE), and third- and fifth-grade students, respectively, read 41 and 77 words per minute on the oral reading fluency passages (Aimsweb). In terms of reading comprehension, the average score for the WRMT-R test of passage comprehension placed students at the 30th percentile, and for the Group Reading and Diagnostic Assessment (GRADE), they scored, on average, at the 23rd percentile.

This sample, as a whole, was substantially less impaired in basic reading skills than most samples used in previous research with older reading disabled students. These earlier studies typically examined samples in which the phonemic decoding and word reading accuracy skills of the average student were below the tenth percentile and, in some studies, at only about the first or second percentile. Students in such samples are much more impaired and more homogeneous in their reading abilities than the students in this evaluation and in the population of all struggling readers in the United States. Thus, it is not known whether the findings from these previous studies pertain to broader groups of struggling readers in which the average student's reading abilities fall between, say, the 20th and 30th percentiles. This evaluation can help to address this issue. It obtained a broad sample of struggling readers, and is evaluating in regular school settings the kinds of intensive reading interventions that have been widely marketed by providers and widely sought by school districts to improve such students' reading skills.

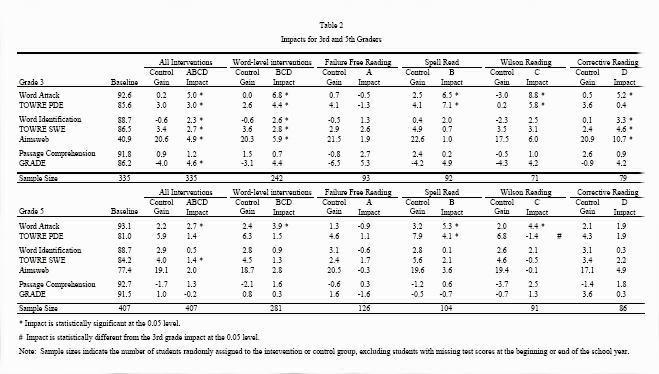

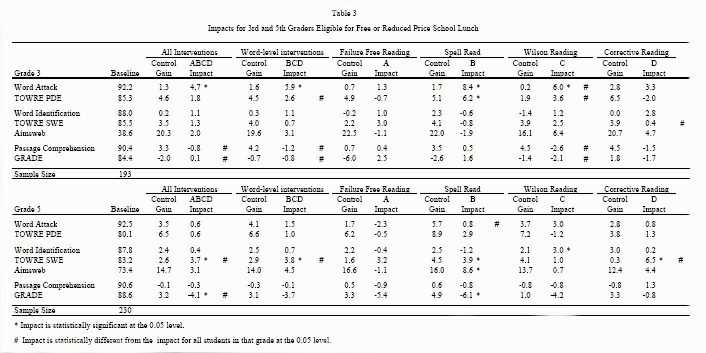

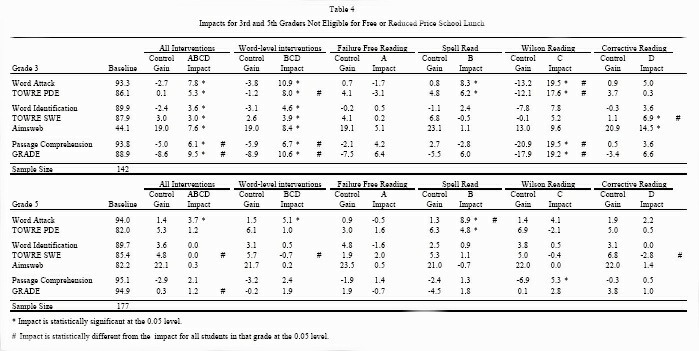

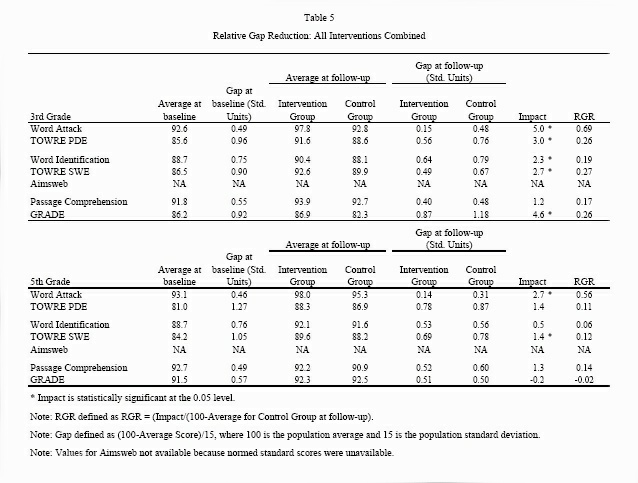

DISCUSSION OF IMPACTS

This first year report assesses the impact of the four interventions on the treatment groups in comparison with the control groups immediately after the end of the reading interventions. In particular, we provide detailed estimates of the impacts, including the impact of being randomly assigned to receive any of the interventions, being randomly assigned to receive a word-level intervention, and being randomly assigned to receive each of the individual interventions. For purposes of this summary, we focus on the impact of being randomly assigned to receive any intervention compared to receiving the instruction that would normally be provided. These findings are the most robust because of the larger sample sizes. The full report also estimates impacts for various subgroups, including students with weak and strong initial word attack skills, students with low or high beginning vocabulary scores, and students who either qualified or did not qualify for free or reduced price school lunches.

[2]

The impact of each of the four interventions is the difference between average treatment and control group outcomes. Because students were randomly assigned to the two groups, we would expect the groups to be statistically equivalent; thus, with a high probability, any differences in outcomes can be attributed to the interventions. Also because of random assignment, the outcomes themselves can be defined either as test scores at the end of the school year, or as the change in test scores between the beginning and end of the school year (the "gain"). In the tables of impacts (Tables 2-4), we show three types of numbers. The baseline score shows the average standard score for students at the beginning of the school year. The control gain indicates the improvement that students would have made in the absence of the interventions. Finally, the impact shows the value added by the interventions. In other words, the impact is the amount that the interventions increased students'

test scores relative to the control group. The gain in the intervention group students' average test scores between the beginning and end of the school year can be calculated by adding the control group gain and the impact.

In practice, impacts were estimated using a hierarchical linear model that included a student-level model and a school-level model. In the student-level model, we include indicators for treatment status and grade level as well as the baseline test score. The baseline test score was included to increase the precision with which we measured the impact, that is, to reduce the standard error of the estimated impact. The school-level model included indicators that show the intervention to which each school was randomly assigned and indicators for the blocking strata used in the random assignment of schools to interventions. Below, we describe some of the key interim findings:

Future reports will focus on the impacts of the interventions one year after they ended. At this point, it is still too early to draw definitive conclusions about the impact of the interventions assessed in this study. Based on the results from earlier research (Torgesen et al. 2001), there is a reasonable possibility that students who substantially improved their phonemic decoding skills will continue to improve in reading comprehension relative to average readers. Consistent with the overall pattern of immediate impacts, we would expect more improvement in students who were third graders when they received the intervention relative to fifth graders. We are currently processing second-year data (which includes scores on the Pennsylvania state assessments) and expect to release a report on that analysis within the next year.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|